FIFTY YEARS AGO ON THIS DAY – 21 March 2024

Fifty years ago today the Government of Canada established the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry. Its purpose was to hold hearings and report on the social, environmental and economic impact of the proposed Mackenzie Valley Gas Pipeline, and to recommend terms and conditions that should govern its construction, operation, and abandonment.

The Liberal government of the day didn’t do this just because it seemed like a nice idea. The proposed pipeline was meeting with determined opposition by Indigenous people in the Northwest Territories, and substantial public concern across Canada about its environmental effects. The New Democratic Party, which held the balance of power in Parliament, made the Inquiry happen, and that it would be chaired by Justice Thomas Berger, as the price of its continued support.

I was living in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, at that time, working for the Inuvialuit on a mapping project for their land claim. They asked me to stay on and assist them in their participation in the Inquiry, which I did. The next three years, during which I acted as advisor to and expert witness for the Committee for Original Peoples’ Entitlement, changed Canada very much for the better, and also set the course for the rest of my working life.

I already knew who Tom Berger was. As a socialist I admired his politics, and we in the Western Arctic were well aware of his role in the seminal Calder case on Indigenous land rights. Yet in the circumstances of Canada’s headlong rush at that time to develop the energy and mineral resources of the North, from Churchill Falls in Labrador to the oil and gas resources of the Mackenzie Delta, I was not optimistic that much would come of Berger’s Inquiry.

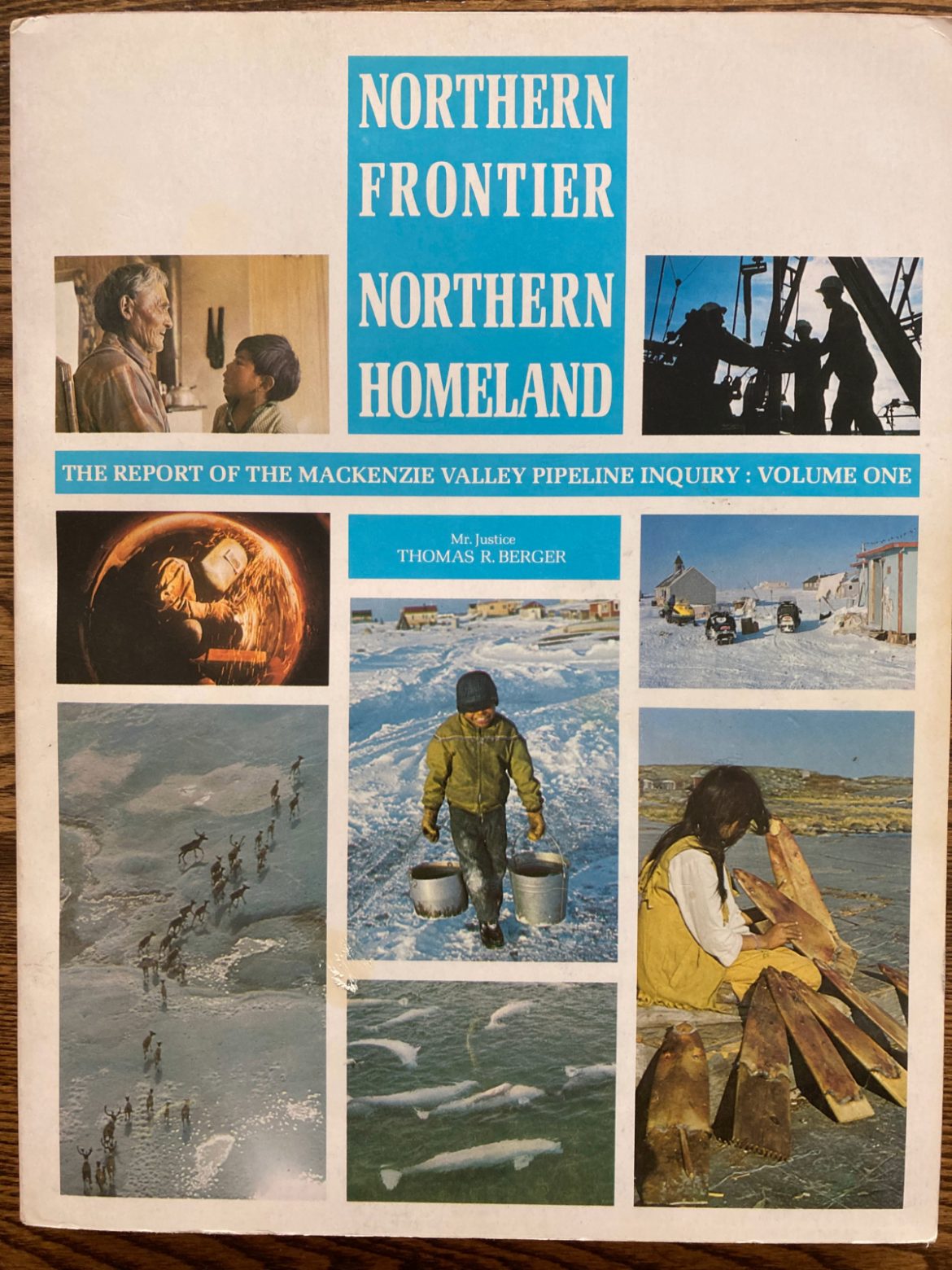

As it turned out, my limited expectations were much surpassed. Not only did Justice Berger recommend against construction of the pipeline unless several key conditions were met, not least the resolution of Indigenous land claims. The very title of his historic report, Northern Frontier Northern Homeland, changed Canadians’ perceptions of the North profoundly and for the better. Canada’s ruling elite, and indeed many ordinary Canadians, thought that the concept of Indigenous title was laughable, that the North was a vast treasure house of riches ripe for exploitation, that its unrestrained development would be unambiguously beneficial, and that there was no need for public consultation and participation on matters of such fundamental national interest. In short, much of what we now believe to be normal and right with respect to Indigenous rights, careful consideration of the environmental consequences of resource development, and public consultation, simply did not exist fifty years ago.

We owe that change in very large measure to Tom Berger’s wisdom and action, and to his courage, his empathy, his capabilities, and his quiet determination. And he didn’t stop there, he continued to act and to advocate for the rest of his life. Individuals do matter in history, and Tom Berger was one of them. To the extent that we live in a better country now than we did then, we owe him a debt of gratitude and honour. He stands in the select company of truly great Canadians.

Tom Berger did not do this alone. His Inquiry succeeded mainly because so many Indigenous residents of the affected communities in the North turned out to express their views and concerns at the community hearings, aided by the key intervenors at the Inquiry, with the Dene and Inuvialuit organizations at the forefront.

Yet nothing is forever. If we do not defend and advance the achievements initiated fifty years ago that made Canada better, they will wither away and we will go backwards.