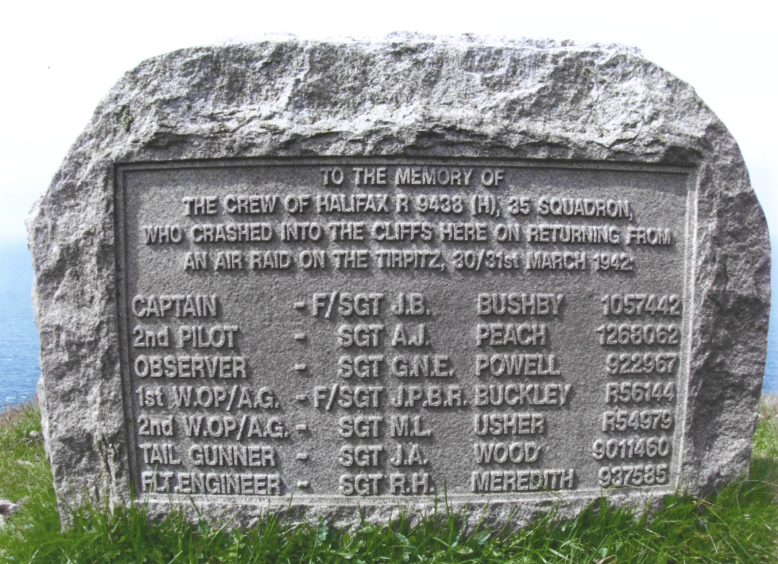

Remembering Canadian Aircrew Buried in Germany

As the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War draws to a close, we might reflect on the sacrifice that Canadians made in those years. The Reichswald Forest Cemetery in Germany provides a stark reminder. There in the quiet serenity of a hardwood forest lie the remains of 7692 British Commonwealth servicemen killed in northwestern Germany. Over…

Read more