Tag Archive: personal reflection

Peter Usher

May 5, 2025

This is my uncle Joey Jacobson’s grave in Lichtenvoorde General Cemetery in the Netherlands. The photo was sent to me by a man I know only because he read my book, Joey Jacobson’s War, a few years ago, and who went out of his way last week to visit Joey’s grave. I was deeply moved that he…

Read more

Peter Usher

May 27, 2024

Huron County is the land of corn, soy, and wheat. If city folk wonder where their food staples come from, this is the place. The land here is bountiful, productive, and readily cultivated. It’s as good as it gets in Canada. Drop a nine-furrow plow in the dark soil and you could go for miles without…

Read more

Peter Usher

March 21, 2024

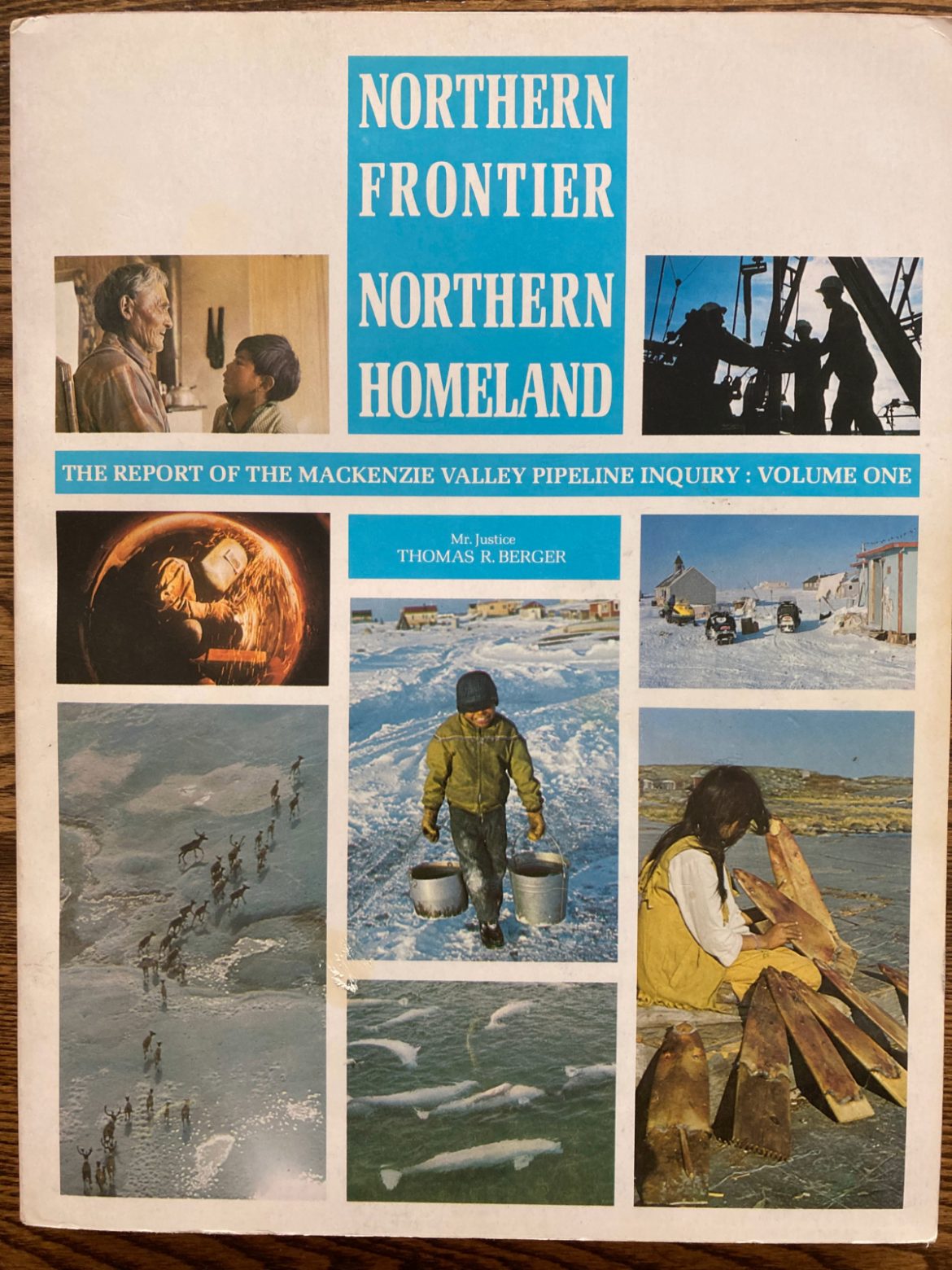

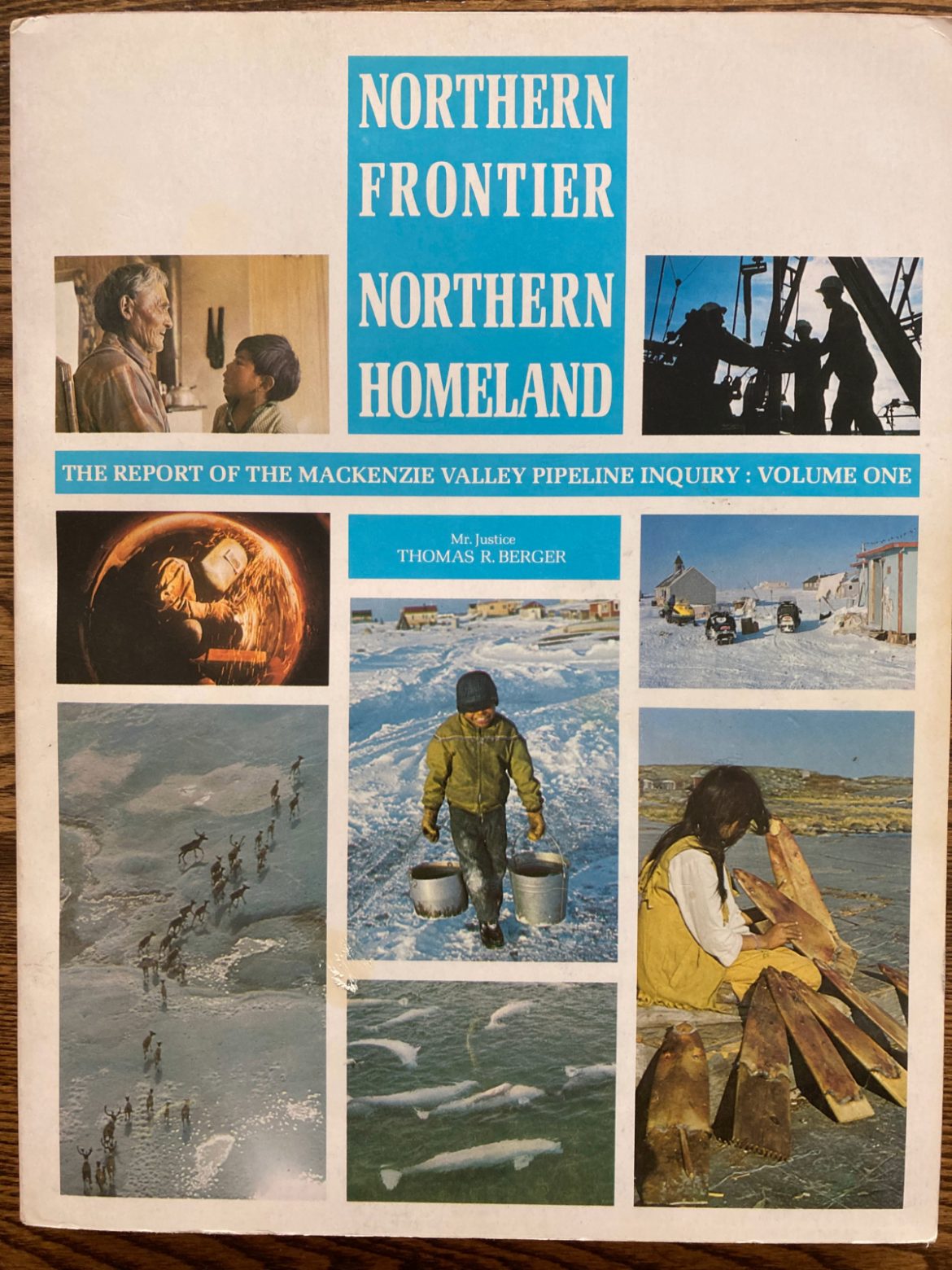

FIFTY YEARS AGO ON THIS DAY – 21 March 2024 Fifty years ago today the Government of Canada established the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry. Its purpose was to hold hearings and report on the social, environmental and economic impact of the proposed Mackenzie Valley Gas Pipeline, and to recommend terms and conditions that should govern…

Read more

Peter Usher

March 11, 2023

One of the consequences of Covid has been rediscovering the joys of snowshoeing. While isolated on a hundred acres of bush in eastern Ontario, with three kilometers of trails, there was never a boring day in winter, whatever the weather. And so it continues. While snowshoeing I read the news: what animals are moving about…

Read more