On This Day — 21 March 1974

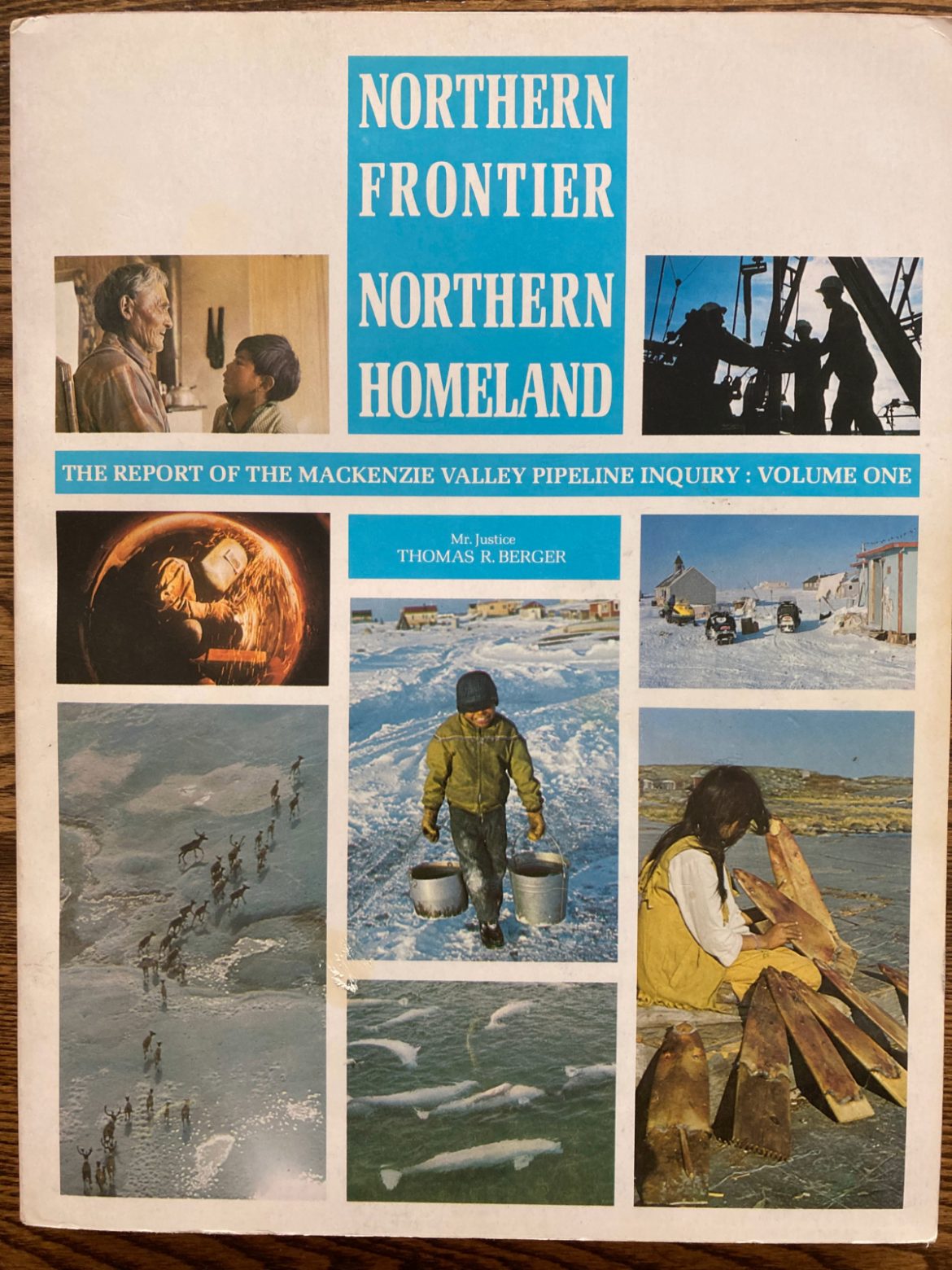

FIFTY YEARS AGO ON THIS DAY – 21 March 2024 Fifty years ago today the Government of Canada established the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry. Its purpose was to hold hearings and report on the social, environmental and economic impact of the proposed Mackenzie Valley Gas Pipeline, and to recommend terms and conditions that should govern…

Read more